Ringrazio Irina Zingg per questo lungo ed esauriente articolo sulla storia dell’arpa in Russia. Un ringraziamento a Isabel Moreton per averci gentilmente concessa la sua pubblicazione. (Emanuela Degli Esposti)

IRINA ZINGG

HISTORY OF THE RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL

(From 18th to the beginning of the 20th centuries)

(The English version of the article has been published in the World Harp Congress Review (Fall 2016, Volume XII, No. 5; Fall 2017, Volume XIII, No. 1; Spring 2018, Volume XIII, No. 2; Fall 2020, Volume XIV, No 1). This revised version is published on the website of Italian Harp Association with kind permission of Isabel Moreton, The Editor of the WHCR).

I. BEGINNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL (18th to the first half of the 19th centuries)

1. EARLY PERIOD

2. BEGINNING

2.1. St. Petersburg

2.1.1. The Smolny Institute

2.1.2.Meschanskoe Otdelenie

2.2. Moscow

3. DEVELOPMENT

3.1. Jean Baptiste Cardon

3.2. From Cardon to Devitte

3.3. Nikolai Devitte

II. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL. BEGINNING OF PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION (From the second half of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th centuries)

1. ST. PETERSBURG

1.1. Conservatory and Albert Zabel

1.2. Russian Court Chapel and Franz Shollar

1.3. Ekaterina Walter-Kühne

1.4. Ksenia Erdely

2. MOSCOW

2.1. Moscow Conservatory and Ida Eichenwald

3. FOREIGN HARPISTS

4. THE RUSSIAN HARP REPERTOIRE

III. FOUNDATION OF THE MODERN RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL. ALEKSANDR SLEPUSHKIN

ATTACHMENTS

1. Appointed harpists to the Imperial orchestras in Russia from the 18th to the 20th centuries

2. Professors at Conservatories in Russia till the Soviet Revolution (1917)

3. Compositions of A. Zabel

I. BEGINNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL

(18th to the first half of the 19th centuries)

1. EARLY PERIOD

According to Russian musicologists, the harp as an instrument was non-existent in native Russian culture.

Some of the earliest evidence of the instrument is found in 1596 in the Russian dictionary Asbukovnik and mentions instrument and players as “arpa, arpista” in the Italian spelling. In later sources “harfa, harfenist” from the German spelling is used (10, p. 175). This leads to the conclusion, that the harp did not belong to native Russian culture, but that it was brought to Russia by foreign visitors.

By the middle of the 18th century, the hook harps were widely spread and used mostly in Russian folk music.

2. BEGINNING (18th century)

The 18th century marked an intensive development of harp playing in Europe, which was greatly influenced by the appearance of the single-action pedal harp, created by Jakob Hochbrucker around 1720.

During the reign of Peter the Great1, musical education became mandatory for the nobility in Russia. The number of musicians and the diversity of instruments increased. Among them was also the harp. Three granddaughters of F. A. Golovin – a field marshal of Peter the Great – “were excellent musicians and showed their art on the piano and at the harp performing in public” (16, p. 5). According to the St. Petersburg and Moscow newspaper Vedomosti, harp was extensively taught and played by foreigners in Russia, mostly of German, but also Bohemian and French origin.

In autumn 1745, Jacob Hochbrucker’s second son Johann Christoph visited St. Petersburg, bringing with him a Hochbrucker pedal harp. In the local newspaper of 1st November 1745 we can read, “He plays … the harp and offers everyone the possibility to hear his music and study his instrument” (18, p. 2). In 1762 Jakob Hochbrucker’s nephew Christian Hochbrucker visited St. Petersburg (10, p. 179)

1 Tzar of the Russian Empire between 1682 – 1725.

2.1. St. Petersburg

2.1.1.The Smolny Institute

The consequence of these two visits was the fact that Russian Empress Catherine the Great purchased a pedal harp from Hochbrucker for the newly opened Smolny Institute in 1764. The Smolny Institute, a boarding school for young girls from noble families, was known as Russian Institute For Noble Maidens. Girls studied beaux arts (fine arts), literature, history, science, mathematics, foreign languages and aesthetics, each of them played at least one instrument. Although the main purpose of the school was to prepare excellent wives for noble gentlemen, we can acknowledge the Smolny harp class first of its kind, on a regular basis, in Russian history.

Fig. 1. K. Beggrov (1799 – 1875). View of the Building of the Smolny, Russia, 1823. The Hermitage Museum1

The first harp teacher in Smolny was Maria Levesque from France in 1774. She arrived in Russia with her husband, historian Pierre-Charles Levesque who had been invited to visit Russia by Catherine the Great together with D. Diderot. “Levesque was an experienced and competent teacher: only after one year her students performed solos and harp duos at the concerts of the Smolny Institute” (16, p. 19). The first graduate of the Levesque class was Glafira Alimova (1758–1826), whose brilliant portrait by Dmitry Levitzkiy, commissioned by Catherine the Great, is very famous. Talented, intelligent and beautiful, Alimova was appointed as Lady-in-Waiting to the Imperial court after graduation.

Source: http://www.encspb.ru/object/2855701438?lc=en

Fig. 2. D. Levitzkiy (1735 – 1832). Portrait of Glafira Ivanovna Alymova, 1775. The Russian State Museum, St. Petersburg1

After Levesque’s departure in 1782, her student Anastasia Semishina succeeded her. Daughter of Pamphil Semishin, the serfman of Count Golitsin, Semishina had extraordinary talents and was an excellent graduate of the Meschanskoe Otdelenie (see below). After graduation she was appointed piano, and later harp, teacher in Meschnaskoe and Smolny. Semishina was the first professional harpist and teacher of Russian origin who had also been educated in Russia. She taught in Meschanskoe Otdelenie and Smolny until 1802.Simon Hartmann – harpist with a solid European reputation – was appointed teacher in Smolny in 1784-1788. Besides teaching at the Smolny Institute, he was a harp trader and taught privately the members of the nobility. His compositions include: Two Sonatas for harp and harpsichord in accompaniment of violin Op. 8, dedicated to Princess E. A. Vyasemskaya, and Three Sonatas op.10, dedicated to Countess Osterman. In 1797 Smolny saw the arrival of a new harp teacher: Henri Noel Le Pen (1766-1849). He was a notable figure in the music world – singer, pianist, composer, and harpist – who left an impact on the development of the harp in the 18th century. For harp, he composed Two Sonatas for harp with violin accom- paniment op. 12, Sonata for harp with violin accompaniment op. 13, Overture “Kalif Bagdadskiy” for harp with violin accompaniment op. 16, Variations on the opera themes “Aschenputtel” by Daniel Steibelt. Le Pen played with the Bolshoi Theatre of St. Petersburg for several seasons. At the end of his life, he went back to France and died there. Next to Glafira Alimova, among the first graduates of Smolny were Ekaterina Nelidova and Anastasia Borscheva – excellent harpists, they pursued careers at the Imperial Court, being also the Imperial Court harpists until the arrival of Jean Baptiste Cardon to St. Petersburg.

2.1.2. Meschanskoe Otdelenie

In 1765 the Smolny Institute opened a branch: a college for girls from middle class families (priests, merchants’ children) called Meschanskoe Otdelenie Obschestva. The main difference from Smolny Institute was the goal of education: here girls were prepared for professional activities, in particular to replace foreign teachers. In the historical perspective for us this fact is important, since the class in Meschanskoe Otdelenie was the first professional harp class in Russia, as early as 1765. At the beginning the same teachers as in Smolny taught there. All the foreign teachers were replaced in 1779 by an alumna of Meschanskoe Otdelenie, the above-named Anastasia Semishina. The period between 1770 and 1810 was a time of intensive visits of foreign harpists to Russia, performers and teachers. Both Moscow and St. Petersburg witnessed a growth in popularity of the instrument in various circles of the society.

2.2. Moscow

Unlike St. Petersburg, where most musicians were foreigners, in Moscow for the most part serfs were musicians at aristocratic families. They were taught by private teachers in order to entertain aristocrats. Although their teachers were the same as in state institutes in St. Petersburg, their education did not have the solidity and roundness that was offered in state institutions of St. Petersburg. One outstanding figure in Moscow was Praskovia Gemchugova – a multi-talented woman: she played the piano, harp, guitar and sang. This personality is particularly interesting, because her harp teacher was Jean Baptiste Cardon. Being a solid musician, he influenced the development of her artistic personality, refined her technique, and broadened her artistic horizons.

Fig.3. Praskovia Gemchugova1

By the end of the 18th century, the harp was a widespread and popular instrument in Russia. Next to professional and “noble” education in state institutes in St. Petersburg, the harp was also taught privately in Moscow. Both professional and amateur players played at high standards. The only difference between them was that professionals made their living from performing and teaching, amateur players enjoyed their playing without depending on their playing for an income. Both foreign and Russian harpists performed and taught at this time.

Source: http://old.superstyle.ru/23jul2010/praskovja_zhemchugova (28.02.2021)

3. DEVELOPMENT (First half of the 19th century)

The development of the Russian harp school is linked closely with the establishment of Russian musical culture in general, in particular with the activity of composers such as Mikhail Glinka, Alexander Alyabyev, and Dmitry Bortniansky, among others.

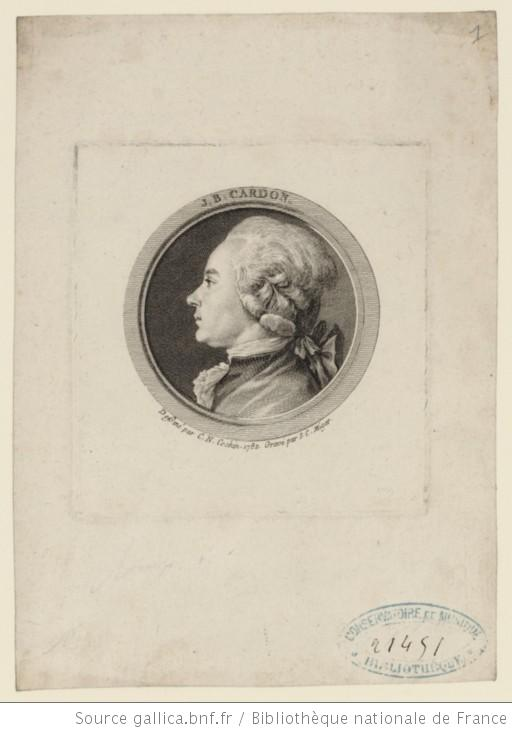

3.1. Jean Baptiste Cardon

One of the major figures in the development of the Russian harp school, both in performance and composition, was French harpist Jean Baptiste Cardon (1760-1803). He was not only one of the most famous harpists in Europe, but had already published one of the first harp methods and established his own school, respectively technique.

Fig. 4. S.- Ch. Miger (1736 – 1820). Jean-Baptist Cardon. Graveur1

Fig. 4. S.- Ch. Miger (1736 – 1820). Jean-Baptist Cardon. Graveur1

Cardon was born in France, his father, uncle and three brothers were court musicians. At the age of fifteen, Jean-Baptiste began serving at the court of Comtesse d’Artois and became her harp teacher. At this early age he began composing, and his first works – Four sonatas and variations for the harp with accompaniment of violin op. 1 – were dedicated to the Comtesse.

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84161936 (26.02.2021).

While Cardon’s reputation as a harp virtuoso in Paris grew constantly, he performed at the “Concert Spirituel”, composed and taught intensively. In 1784, at the age of 24, he published his harp method book L’art de jouer de la harpe. Leaving France about 1785, it is not clear when he first arrived in Russia. By September 1790 Cardon was appointed harpist at the Imperial Court in St. Petersburg, performing intensely with the great musicians of the time. From 1793 on, his official title was “Professor, harp, in the service of the Russian Imperial Court”. Among the Royal family members who had lessons with Cardon, were Elisaveta Alekseevna, (wife of the future Emperor Alexander I), and Elena, (daughter of Pavel, heir to the Tzar throne). Cardon dedicated to the latter his Three sonatas op. 11. Elena Pavlovna was going to be married to the Prince of Mecklenburg-Schwerin: leaving Russia, she took with her her most important possessions: the harp and her music library1. Teaching took significant part of Cardon’s life. A most interesting aspect of teaching in the Russian musical world at this time was the scope of social classes. Musical training was not limited to royalty or even to the upper class. In Moscow, Cardon prepared serfs (who were freed in Russia in 1861) for professional performance work to entertain aristocrats, whereas in St. Petersburg he taught harp to the Grand Duchess for future amateur playing. In his compositions Cardon reflected his involvement and close association with Russian musical culture. He often used Russian folk songs as thematic material in his compositions. In his Russian period Cardon’s compositions include Four Quartets for harp, violin, viola and bass, Three Sonatas op. 10, and Three Sonatas op. 112 . In 1797 Cardon started publishing a weekly harp journal, the Journal of Ariettas, which had an important impact on the development of the Russian harp culture. In the surviving thirty-four editions, six of them included pieces for solo harp, the others were popular Italian ariettas and romances. Using the Russian folklore as thematic material, these issues were pedagogical repertoire, which he used in his teaching. It was also his intention to make harp playing available to all levels of society, thus democratizing the harp and its repertoire. Some surviving issues are historical documents, proving the high level of harp culture in Russia in those days.

1 A large selection of J. B. Cardon scores are kept at the library in Schwerin, Germany. (16, p. 15).

2 According to Tugai, most probably Cardon started a new numeration of his compositions after his arrival in Russia: Cousineau’s catalogue counts 22 opuses before Cardon’s departure from France (16, p. 16).

An important achievement of Cardon’s in historical perspective, is the enrichment of harp texture by developing numerous different types of arpeggio, giving it expressivity. In Russia, Cardon is seen as an explicit link in teaching, in virtuosic performance, and particularly in composition, with the European traditions that influenced the Russian harp development. In return, Russia gave Cardon all the necessary conditions to shape his talents. Today his heritage is an essential part of the Russian harp culture.

3. 2. From Cardon to Devitte

Imperial Theatres of Moscow and St. Petersburg were essential part of the cultural scene of Russia. Since the end of the 18th century there were appointed and invited harpists, starting from Cardon’s appointment. The list of well-known names continues to the beginning of the 20th century (see Attachment 1). Next to Cardon, another foreign harpist who influenced the development of harp culture in Russia was Czech Albert Fisher: since 1794 he lived and worked in Moscow. While comparing the influence of Fisher and Cardon on the development of the harp in Russia, Pokrovskaya states: “Fisher’s creativity was based on Russian folklore – he often played Russian songs on the harp, stimulating the establishment of Russian harp repertoire based on folk material. His students’ playing was marked by intimacy and melodiousness – the features, which later would become one of the main peculiarities of Russian instrumental performing school. Cardon and his pedagogical activities were encouraging professional development of harp playing, which emphasised the European influence” (10, p. 209). The years between 1812 and 1845 were a flourishing time for the harp in Russia. Russian composers wrote for harp solo and chamber music with the harp. The first harp manufacture workshop opened. Russian professional and amateur harpists intensively performed in their repertoire harp concerts and brilliant concert pieces by Dussek, Bochsa, Naderman, de Marin. Erard harp was becoming more and more popular in Russia, and a number of European harpists visited Russia with concerts: in 1830 Alina Spadi Bertrand (1830), Kasimir Bekker (1837), Robert Nicolas-Charles Bochsa (1840), John Thomas (1852). Another noticeable figure in the Moscow harp scene was Carl Shulz. Born into the family of an instrumental master, his brother George1 and himself learned to play the harp in England, before the family moved to St. Petersburg at the beginning of the 19th century. The harpist had a great temperament and melodious sound. Schulz intensively performed and taught in Moscow, he was popular and loved by Moscow public. Carl Shulz was the teacher of Nikolai Devitte – first Russian harpist, who attained international recognition.

1 George Shulz was appointed harpist at the Imperial Theatre orchestra in St. Petersburg

3. 3. Nikolai Devitte

“Celebrated Moscow harpist”, responded Mikhail Glinka about Nikolai Devitte (1812 – 1844), while the newspaper Morning Post mentioned him as “world’s most brilliant and best harpist” (10, p. 248). Nikolai Devitte was born in 1812 into the family of an engineering general. Aged 8, Nikolai started to learn to play the harp under Carl Shulz’s guidance. At 10, he gave his first public performance, at 12, he performed Concert by Bochsa and began his first atempts as a composer. Conforming to his family expectations, he pursued a military career and became a hussar.

Fig.5. Nikolai Devitte1

In 1834 Nikolai Devitte quitted the military career and took an active part in the cultural life of Moscow. Highly skilled amateur instrumentalists insured the intensity and high level of the Moscow musical life. These led to the establishment of the Moscow Musical Assembly – proving that the performing art of amateurs was becoming a national value. Nikolai Devitte became one of the most active personalities in the Assembly. An important event in the harp life in Russia was the premiere of Glinka’s Septet Anna Boleyn in 1834. There is no direct evidence that the harp part was performed by Devitte, but a number of features confirm that Nikolai Devitte performed with Mikhail Glinka. Glinka had a very high opinion of Devitte’s playing. In 1835 a dramatical event occurred, which changed the life of Nikolai Devitte. General Devitte, the harpist’s father, was put on trial and deprived of the privileges of the nobility. Nikolai Devitte became now the family bread winner, and started to teach. His status changed from an amateur to professional harpist, and for the following nine years his life intertwined with the harp. Nikolai lived in Moscow, where he taught, performed, composed. In 1841 Bochsa visited Moscow, but was not successful as a harpist, because Devitte was not less skilled than Bochsa. The meeting with the famous European harpist forced Nikolai Devitte to trust himself. In 1843 Nikolai Devitte became the “Harpist at the Imperial Court” – being the first Russian harpist to hold this position. In the same year Nikolai Devitte undertook a European tournee, started in Riga. Followed by Sweden and Ireland, Devitte immediately won the admiration of his audience. Dublin newspapers stated: “for sure… Mr. Devitte unites in his play all the best features of such great artists as Dussek, Krumpholz, Labarre and Bochsa… He overtops them all… Most elegant artist of our days…” (10, p. 245). In January 1844 Devitte arrived in London. The following day after his first concert, the Morning Post wrote: “…the greatest artist… his sound smooth and rich, delicate yet energetic, his trills – are perfection… his scales are impressive… most admirable in his play is cantabile … in his hands harp speaks, sings and full of lively sound…” (10, p. 246). A month after his London’s debut, the Morning Post notified the sudden death of the artist. Nikolai Devitte was 32 years old.

Source: (17, p. 1).

Fig. 6. Autograph of Nikolai Devitte1

Source: (17, p. 1).

In the face of Nikolai Devitte, Europe admitted the excellence of the Russian performing school. He impressed the listeners with his mastery, expressive power, endless variety of sound and cantabile – features, inherited from the Russian performing school.

II. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL.

THE BEGINNING OF PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

(From the second half of 19th to the beginning of the 20th centuries)

The development of the Russian harp culture in the 19th century was influenced by different factors, such as extended performing traditions by talented amateur-players since the 18th century as well as dedicated work of national and foreign professional harpists. As a result, a Russian harp repertoire began to develop. Mikhail Glinka, the ‘father’ of Russian music, with his esthetical views and compositions influenced the development of all instrumental performing schools in Russia. Regarding the social background, the abolition of serfdom in Russia in 1861 led to rapid changes in the economic, social and cultural life. In the world of music, the establishment of the Russian Imperial Music Society in 1859 played an important role.

Nevertheless, in mid-19th century, after a flourishing period at the beginning of the century, the harp culture witnessed a regression: the harp was heard less and less in concerts, there were less talented and educated harp players and pedagogues, almost no new solo repertoire was composed. After the harp class in Meschanskoe Otdelenie was closed, harp could be studied only under the guidance of private teachers, unregularly and without any complete educational system. Qualified pedagogues taught in the Institutes for noble Maidens: Smolny, Ekaterininsky, and Elisavetinsky. Here young aristocratic girls were not prepared for professional career in music, but for social purposes.

The teaching of other instruments was experiencing the same situation. Therefore, the demand for highly-qualified professionals, led to the opening of St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1862 and Moscow Conservatory in 1866.

1. ST. PETERSBURG

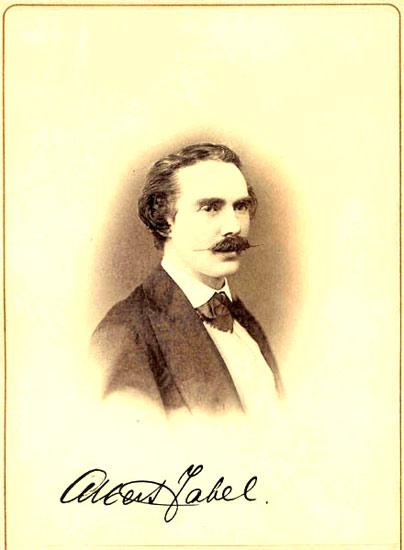

1.1. Conservatory and Albert Zabel

The establishment of a harp class in St. Petersburg conservatory is connected to the name of the German harpist Albert Zabel.

Fig. 7. St. Petersburg Conservatory (around 1900)1

Celebrated soloist, teacher, composer, founder of the harp class at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Albert Zabel is credited with introducing the Berlin harp school to Russia. For most of his career, which lasted over 50 years, he lived in St. Petersburg, the Russian capital at that time. His work The Method for the Harp, published in 1900, was the first methodological work ever written in Russia for the double-action harp. Being a contemporary of P. Tchaikovsky and an experienced and talented orchestra player, Zabel arranged a number of ballet cadenzas: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s (Swan lake, Sleeping Beauty, Nutcracker), Ludwig Minkus’s (Don Quixote, La Bayadère, Paquita), Adolphe Charles Adam’s (Le corsaire), which are still performed today at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. Albert Zabel was born in Berlin into the family of Heinrich Zabel. He began to play the harp at the age of 8 – learning it by himself. He acquired such mastery that when Giacomo Meyerbeer heard him play, he immediately appreciated his talent, and helped him to obtain a scholarship at the Berlin Institute for Church Music, where he studied with Karl Grimm.“…Within two years Grimm realized, that his young student surpassed his own skills and frankly admitted this to him” (10, p. 262). Soon after, an invitation from the conductor Joseph Gungle followed to tour with his orchestra Europe and America. On those tours, besides playing in the orchestra, the young harpist also performed harp solos with great success. In 1848 Zabel was appointed solo harpist at the Berlin Opera.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stpetersburgconservatory1900.jpg (28.02.2021)

Fig. 8. Albert Zabel1

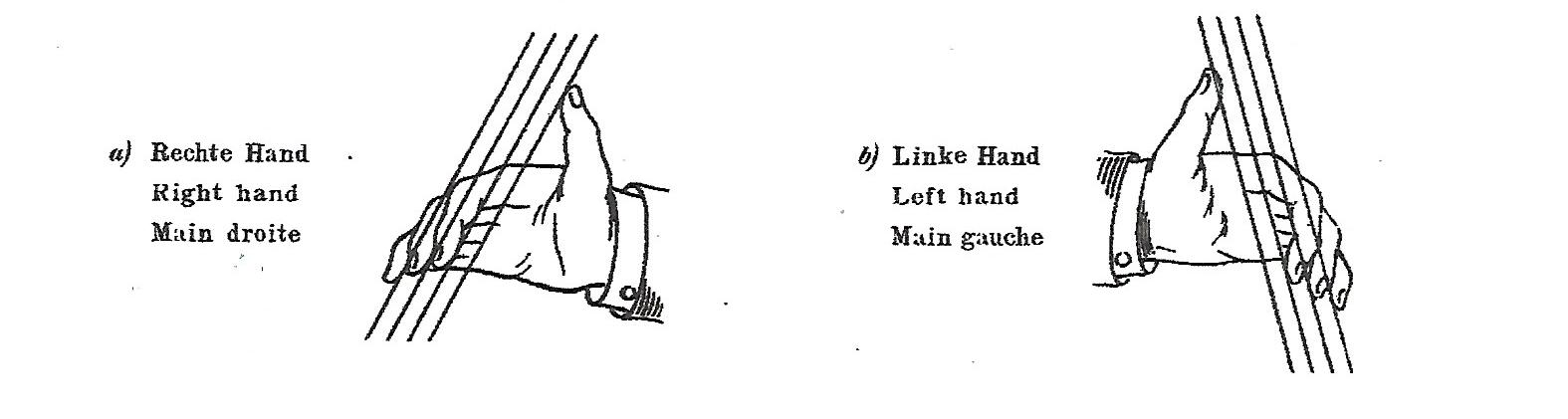

At the beginning of 1850, Gungle’s orchestra was regularly invited to play at the summer music seasons in “Pavlovsk’s Music Train Station”, entertaining the St. Petersburg aristocracy. Zabel`s solo performances in 1853 were warmly welcomed in the local newspaper St. Petersburg News: “…Lots of brilliance but also many challenges” (15). In 1854 Zabel was invited to join the orchestra of the Italian Opera in St. Petersburg. In addition to his orchestral duties, he continued his brilliant solo career. Soon after, he was invited for a solo harp position at the orchestra of the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, where his orchestral career continued till 1905. Zabel continued to play in the summer seasons of Pavlovsk Station and later with the orchestra of Johann Strauss. Prominent Russian composer and critic Aleksandr Serov wrote in 1856: “In Strauss` s program… you can hear very special performances, for example the harp solos, performed by the young highly gifted harpist A. Zabel” (14, p. 158). Zabel’s artistry was appreciated by many Russian composers. Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov called him “the peak of perfection” (16, p. 78). Having gained the reputation as a harp virtuoso, Zabel continued his brilliant career as a solo harpist till the beginning of the 20th century, i.e. for more than 50 years. “Full and deep sound, brilliance, nobility of interpretation, sense of form ; … charming melodic tone in both forte and piano … if to add to this incomparable quality his flawless technique, we get a portrait of the harpist Zabel”- says the author of the first Russian harp monograph, Ivan Polomarenko (12, p. 90). In 1900 Zabel wrote his renowned The Method for the Harp. This book appeared in German, French and English (not in Russian), commissioned by the publisher Zimmermann and dedicated to Alphonse Hasselmans. Zabel was “…against the word school, … but as I want to be the students’ friend and adviser, I will make them acquainted with the most essential conditions necessary to the development of the fingers, the mechanical proficiency and the tone” (19, p. 13). An important goal for the harpist was the production of a fine tone: “a silvery tone, full of soul and poetry” (19, p. 12). “…for the formation of a fine tone strength is necessary: and this strength is achieved thanks to the following position of the fingers: ….”:

Fig.9. Position of right and left hands. A. Zabel. The Methode for the Harp. 1

The high thumb and low fourth finger, control over the slightly curved third finger joint, elasticity of the wrist, stable position of the hand during the playing, placing the fingers in the direction of playing, independent work of the fingers, accuracy in placing the fingers on strings without noise, sufficiency of pedal technique – are important basics of the Zabel’s technique. The Method also provides a sample list of recommended pieces (Parish-Alvars, Hasselmans, Thomas) and exercises (Bochsa). Another theoretical work of Zabel’s – Ein Wort an die Herren Komponisten über die praktische Verwendung der Harfe im Orchester – was published in 1899. The harpist aims „…to explain some speciality about the harp and to give friendly advice to composers“ (16, p. 79). Recommendations of the harpist are based on his long-time experience as the orchestra musician. In 1862 Anton Rubenstein, the founder of St. Petersburg conservatory, invited Zabel to join the faculty, where he became professor in 1879, and was raised to the status of “Distinguished Professor” in 1904. Founder of the Russian `St. Petersburg` harp school, Zabel educated many talented harpists, who pursued and further developed his method. Some of them (Dmitri Andreev) – became soloists, some others dedicated their life to the orchestra work (Ivan Pomazansky, Ernst Freygan, Matvei Sereda), some to pedagogical work (Ida Zabel – Rashat). One of his favorite students was Ekaterina Walter-Kühne. The students of the class were very different: they belonged to different social classes, were different ages (most were adults), and obtained various levels of preparation. The first Conservatory graduate was Ivan Pomazansky (1848-1918). After graduation in 1868 with a silver medal, he joined the orchestra of Mariinsky Theatre, where he played almost half a century (35 years by the side of his professor), both in ballet and opera productions. Ernst Freygan was a solo harpist first for Riga Opera Theatre, and later he replaced G. Shulz in the Mariinsky Ballet orchestra. Dmitri Andreev, one of the last students of Zabel, “harpist with great technique and melodious sound” (16, p. 93), dedicated himself to the solo career: besides recitals in Paris, London, Berlin, he was a devoted propagandist of the harp in Russia, travelling and performing in remote Russian districts, introducing the harp to the wider audience. Andreev was the first Russian harpist who recorded for the gramophone plate (harp part in Romance Hesitation2 of M. Glinka with Aleksandr Verzhbilovich, cello). Zabel’s student and daughter Ida Zabel-Rashat became his colleague at the Conservatory in 1896. One of her most talented students was Joseph Yurman, he was accepted at the orchestra of Mariinsky as “outstanding performer” (16, p. 95). Yurman was professor at Leningrad (St. Petersburg) Conservatory, where he taught accomplished Russian harpist Lidia Gordzevich. In 1905 Albert Zabel left his teaching post due to his illness. Being partly paralysed, he “daily tuned his harp and played with the left hand”- writes Polomarenko (12, p. 90 ).

1 Source: (19, p. 12).

2 Somnenie (Сомнение).

1.2. Russian Court Chapel and Franz Shollar

Beside Albert Zabel, the representative of the Czech harp school Franz Shollar, (1859 – 1938) left an exceptional mark in Russian musical culture – in fact, for two instruments: the harp and the horn. Student at Prague conservatory of Václav Staněk, he arrived in Russia in 1883. Being a soloist at Mariinsky theatre first as a hornist, later as a harpist, he taught, beside the horn class, the harp class from 1886 to 1922 at the Russian Court Chapel, where the level of teaching was high – indeed, every singer had mandatorily to learn how to play an instrument.

Fig. 10. Russian Court Chapel1

Talented pedagogue, Shollar had a structured and effective teaching system. We can only regret, that this harpist did not leave any methodological work for the harp, as he did for the horn: School for the Horn is still actual today. As for the harp, we rely on the Master’s proud words (1912): “… my numerous students work in different orchestras, among them – Mariinsky Theatre, Russian Court Orchestra etc…” (16, p. 115). Among Franz Shollar’s students, let us mention Nikolai Amosov, Nikolai Parfenov, Daniil Grigoriev, V. Kanischev, Ivan Polomarenko. Shollar’s daughter and student, Maria, became a soloist at Mariinsky Theatre in 1907, replacing August Insprucker.

Source: http://kapella1.chat.ru/ist.htm (28.02.2021)

1.3. Ekaterina Walter-Kühne

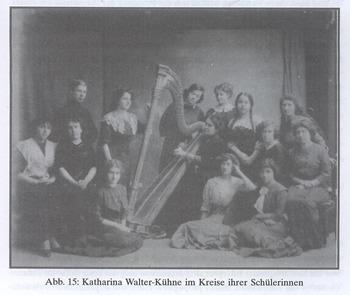

One of Zabel’s favorite students, Ekaterina Walter-Kühne (1870 – 1930), was an important personality in the Russian harp scene. She continued the traditions of her teacher and followed his footsteps as a soloist, in the orchestra, and in pedagogy. Born in St. Petersburg into a German family, as a young girl she early displayed musical talents, and at the age of 11 she entered St. Petersburg Conservatory to study harp with A. Zabel and piano with K. Lutch. In 1888 she graduated from the conservatory and, on the advice of A. Rubinstein, she decided to totally devote herself to the harp. Walter-Kühne’s playing was distinguished by its artistry, emotion, power and rich sound. A brilliant performer, she enjoyed enormous success with the St. Petersburg public. The harpist was often heard in the concerts of the Imperial Music Society. Her repertoire included works of E. Parish-Alvars, A. Hasselmans, Ch. Oberthür. In 1907 Walter-Kühne gave a Russian premiere of the Concerto for flute and harp K. 299 of W. A. Mozart. Besides that, she often appeared in the aristocratic salons of St. Petersburg, where the harp at this time received its wide recognition. There, “her programs reflected the popular tastes of the socialites… and included – very successfully – her own fantasias on themes from popular operas such as Rigoletto, Faust, Eugene Onegin ” (5, p. 291). From 1903, Walter-Kühne was a soloist of the orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre. Her pedagogical activities include teaching: from 1891 – at Smolny, from 1904 – to 1917 at both Smolny and at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Among her students – Anna Gelrod (soloist of the Kharkov Opera and professor at Kharkov Conservatory), Eleonor Damskaya (to whom Prokofiev dedicated two of his harp pieces), Maria Gorelova (she shared the First Prize with Vera Dulova at the 2nd All Union Competition in 1935, soloist of the Bolshoi Theater orchestra) and, of course, one of her favorite students – Ksenia Erdely.

Fig. 11. Ekaterina Walter-Kühne with her students1

In 1917, after the Soviet revolution, Ekaterina Walter-Kühne emigrated with her family to Germany and settled in Rostok, where she spent the remaining years of her life.

1.4. Ksenia Erdely

Ksenia Erdely (1878 – 1971) – an outstanding Russian harpist, was one of the most influential personalities in the Russian harp world of the 20th century. She lived a long, artistically full, outstanding, accomplished life, which she sincerely shares in her Memoirs book Harp in My Life. This article is going to deal with the beginning of her career, which belongs to the reviewed period. After graduation from Smolny in harp, piano and choir conducting, she decided to devote her life to the harp, as it would give “possibilty … for independent creative aspirations and achievements” (2, p. 36) In 1899 Erdely became a soloist at the Bolshoi Theater orchestra in Moscow, and from 1900 her 70-year long pedagogical career began: firstly, in Drama-Musical College of Moscow Philharmonic Society, starting from 1904 – in Ekaterininsky Institute. After marrying, she moved to St. Petersburg, and took over Walter-Kühne’s class: in 1911 – in Smolny, in 1913 – in St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Source: http://www.sophie-drinker-institut.de/cms/index.php/kuehne-catherine (15.02.2021)

Fig. 12. Ksenia Erdely1

Her active concert life as a recitalist took her around Russia, she worked intensively on the development of the harp repertoire: doing transcriptions, or premiering in Russia European harp repertoire. In 1909 Erdely premiered in Russia Introduction and Allegro of M. Ravel (with Aleksandr Ziloti’s orchestra). In her book Ksenia Erdely shares precious memories: in 1910 she performed the Fantasy by Théodore Dubois. “…Beside general public, some of my friends, too, attended the concert. How big my surprise was, when I saw A. G. Zabel sitting in the first row. Some years earlier he had suffered from apoplexy, and he had to stop his performing career… . That day he determinedly asked to be taken to the concert, to hear the new harpist and to get to know her. Albert Genrichovich was very gentle and kind to me… I was very touched by such attention. And now, after some 60 years, I remember the great Master – who was also a person of great feelings and a big heart” (2, p. 86). That was a remarkable meeting of the two Masters: one from the 19th century and another one from the 20th century. Ksenia Erdely, who was a devoted student of Zabel`s student, E. Walter-Kühne, being Zabel`s harp “grand-daughter”, continued and developed his traditions throughout her outstanding career.

Source: https://mugi.hfmthamburg.de/old/A_lexartikel/lexartikel.php%3Fid=erde1878.html (28.02.2021)

2. MOSCOW

2.1. Moscow Conservatory and Ida Eichenwald

German harpist Ida Eichenwald (1842 – 1917) was the first harp professor at the Moscow Conservatory, “she…influenced the establishment of Moscow harp school in a similar way, as Zabel – the St. Petersburg” (3, p. 102).

Fig. 13. Ida Eichenwald1

She was Karl Grimm’s student, and she enjoyed her successful Berlin debut in 1855, followed by the European tour alongside her pianist-brother. After the St. Petersburg concert in 1860, she drew attention with her “excellent technique, exceptionally beautiful and full tone quality complemented with filigreed phrasing” (16, p.102). Consequently, she was offered the solo harp position at the Mariinsky Theater. Later in Moscow, she held a position of solo harpist at the Bolshoi Theatre orchestra between 1864 and 1901. Eichenwald worked as a harpist for the Russian Imperial Music Society orchestra. She also appeared as a harp soloist in solo recitals.

Ida Eichenwald was the first professor of harp (1874 – 1906) at the Moscow conservatory.

Source: http://cultureru.com/tag/ida-ivanovna-eichenwald-1842-1917/ (28.02.2021)

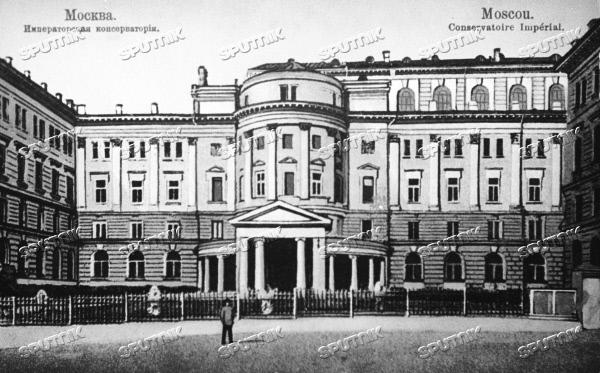

Fig. 14. Moscow Conservatory1

According to Taneev, “her outstanding technique with beautiful, full tone and refined phrasing – makes a charming impression on the public” (10, p. 268). The first student who graduated from her class in 1880 was Elizaveta Dmitrieva. Among her students at Moscow Conservatory let us mention Nadegda Sokolovskaya, N. Anisimova – later harpists of the Bolshoi Theatre – and acknowledged harp pedagogue Klementina Baklanova. A special place in the Russian harp culture goes to Vladimir Lukin (1875 – after 1918), one of Ida Eichenwald’s last students.

Graduated in 1902 with a Silver Medal, Lukin dedicated his life to a career as a solo harpist. But his main devotion was composition: author of twenty-five compositions – mostly lyrical pieces, as well as Grand Sonata and “Fantasie on Opera “Sadko” – which are rich in melodious material. Lukin was a propagandist of the harp and his aim was to create a real Russian repertoire for his instrument, even though most of his contemporary harpists had in their repertoire pieces of European harpists-composers (Bochsa, Verdal, Parish-Alvars)1. Vladimir Lukin taught the harp class at Moscow Philharmonic College between 1906-1908 “which proves his high professional authority, as the teaching level there was higher, than at the Conservatory” (16, p. 109).

V. Lukin’s compositions were released by the following publishers: Bessel, Jurgenson (Russia), Henry Lemoine (France), Lyra Music Company (USA) (16, p. 108).

Source: http://sputnikimages.com/media/614503.html (27.02.2021)

3. FOREIGN HARPISTS

Despite national harpists were educated and achieved a good preparation at both conservatories, the demand of orchestras for highly qualified harpists could not be yet fulfilled. Therefore, foreign harpists continued to work in Russia, till the Soviet Revolution in 1917. High salaries and good work availability were attractive to them. The earliest Russian harpists having graduated at the conservatory and educated in the country were Ekaterina Walter-Kühne (Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg) and Ksenia Erdely (Bolshoi Theater in Moscow) Among the foreign harpists, who worked in the orchestras in Moscow and St. Petersburg and influenced the Russian harp scene were talented Italian sisters Giannina and Virginia Ciarlone, Czech harpist, student of Hanus Trnecek, Heinrich Ome, Italian Adalgisa Mollica (student of H. Renie and A. Hasselmans), German August Insprucker – first teacher of the Aleksandr Slepushkin. Virginia Ciarlone, harpist at the Imperial Court, was the only one of the few harpists in Russia, who learned to play the chromatic harp of Pleyel-Lyon, but “refused to open the course at the Conservatory” (16, p. 113). She showed interest in and respected the Russian repertoire, enriching the harp repertoire with her transcriptions of pieces, among others: P. Tchaikovsky’s Sentimental Waltz, a romance of A. Rubintstein The Night. Compared to the first half of 18th century, there was a reduced number of solo harpists, who visited Russia. In a historical perspective, it would be interesting for us to follow the visit of the young Wilhelm Posse1, who later, with his student Aleksandr Slepushkin, would play a pivotal role for the Russian harp culture. In 1887 M. Krause wrote the following about Posse’s trip in Russia in the Musical Weekly Sheet. Young Posse “… received an invitation to perform at the Theatre Chapel in Tiflis. His father and mother were for a long time uncertain whether to accept the invitation. Only after hearing, that in Russia young artists could easily earn funds to purchase a double-action harp, his determined parents let the boy travel to a remote Caucasus town. Accompanied by his faithful father, young Wilhelm set off on his first journey in May 1863. The plan worked, the summer-month tours into the mountains brought a rich income. A kind patron Grand Duke Michael granted a stage charity concert. And so, after one and half year stay Wilhelm could come back home. The way home was shaped into a concert tour, which led him through the Krym peninsula, Odessa, along the Don, where the boy performed for Hetman of Cossacks Prince Grobov in Novočerkassk. Travelling through Nizhny Novgorod, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Bromberg the family went back to Berlin…” (7, p. 328).

Information about Posse’s visit, included in the earlier version of this article, published in the World Harp Congress Review, differs: “… with his father flutist, he toured the South of Russia in 1862-64: first playing in the orchestra of Italian Opera in Tiflis, later Wilhelm performed recitals in Odessa” (16, p. 119) Thanks to a recently well-founded source (7) we could discover more details about this trip.

4. THE RUSSIAN HARP REPERTOIRE

As we mentioned above, the 19th century is the time when the school of Russian composers established. This was obviously influenced by changes in social, political and cultural life. Russian composers achieved in their major works, such as operas and symphonies their search “…for ethnicity, their own musical style and language. Solo and chamber music stayed in the background “ (16, p. 121). Although the double-action Erard harp was welcomed and accepted by Russian composers, they saw its proper place just in the orchestra. Very appreciative of the color and timbre possibilities it offered, they extensively used the harp in their scores, also assigning it important solos: Aleksandr Dargomyzhsky, Modest Mussorgsky, Aleksandr Borodin, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, Aleksandr Glazunov, Anton Rubinstein, Sergey Taneyev.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in his letter to Nadegda von Mekk reflects on the harp: “Harp is a wonderful, beautiful instrument with its timbre …, but it cannot be an independent instrument on its own. It has no melodical features, but it is suitable for the harmony… chords and arpeggios – this is the harp sphere” (16, p. 123). The composer had known Ida Eichenwald, who first performed the harp part in the Ballet Swan lake, Overture-Fantasy Romeo and Juliet, Fantasia for orchestra Francesca da Rimini, premiered in Moscow. Tchaikovsky’s ballet cadenzas are available in two versions: the author’s and A. Zabel’s. Tchaikovsky highly praised Zabel – “an artist, whom I highly respect” (16, p. 123) – and was thankful to the harpist, who did reductions of many of the composer’s harp parts. The only original solo piece written for the harp at the time was dedicated to Ksenia Erdely – Prelude by César Cui. At the beginning of the 20th century there was an increased interest in the harp as a concert instrument. Composers included the harp in their chamber works: Three Trios (Nocturne, Barcarole, North Star) by Yuri Sakhnovsky, Nocturne by Nikolai Roslavets, Psalm by Sergey Lyapunov. Also, a new epoch for solo harp repertoire started: Sergey Prokofiev composed Prelude C-Dur op.12 No. 7 (1913) and Piece Eleonora (1915). Numerous compositions were dedicated to E. Walter-Kühne: Mikhail Vladimirov – Waltz Wandering lights, A. Tarutin – pieces Barcarole, Masurka, Evening song, Elegy and Waltz; Feodor Akimenko dedicated his Consolation op. 22 (1904) to Ivan Polomarenko, who also composed for his instrument. (16, p. 126). Another group of harp composers are the harpists themselves. In addition to A. Zabel, E. Walter-Kühne and V. Lukin – as mentioned above, the Czech harpist (while working in Kiev) Agnes Fallad-Shkvor composed «Fantasie – Ukraine» (op. 29), N. Toyman-Shetokhina dedicated her «Hungarian Rhapsodie» to S. Onoprienko. The last group of composers, who invested in the Russian harp repertoire are the Russian composers, who lived abroad – Aleksandr Grechaninov, Foma Gartman, Nicolai Berezowsky, among the others. In 1930 Grechaninov composed in Paris Fantasie Baschkiria for flute and harp op. 125, dedicated to Marcel Grandjany. Other compositions of his are Harp Album and 5 Easy Pieces for harp solo (1943). Berezowsky is the author of the Concerto for harp.The beginning of professional harp education in Russia is connected with two harpists of German origin and representatives of the Berlin harp school of Karl Grimm – Albert Zabel and Ida Eichenwald. Let us not forget Nikolai Devitte, who achieved his best results while connecting in his creative work amateur and professional harpists from Moscow and St. Petersburg. Zabel and Eichenwald brought to Russia the European harp culture, which enriched the Russian one and gave a new impulse to its development. Next to native Russian professionals, many foreign harpists left their mark in Russia: they fitted in with Russia and Russian culture to a different extent, though. All this paved the way and created the favourable conditions for the appearance and outstanding career of Russian harpist Aleksandr Slepushkin (1870 – 1918). With the development of the new methodological principles, which were deeply connected with the best traditions of Russian instrumental performing schools and based on the Russian musical esthetics in general, Slepushkin is considered today as the founder of the modern Russian harp school.

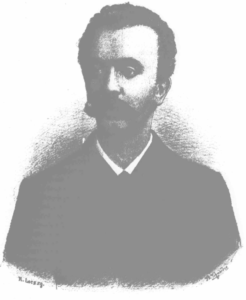

III. FOUNDATION OF THE MODERN RUSSIAN HARP SCHOOL. ALEKSANDR SLEPUSHKIN

Harp-virtuoso, fine musician, great pedagogue and harp-methodologist, Professor at the Moscow Conservatory, Soloist at the Bolshoi Theater, founder of the Russian harp school – Aleksandr Slepushkin had an outstanding career. After resigning from a successful military career at the age of thirty, he dedicated to the harp the following sixteen years of his life, thus having a fundamental impact on the future development of the harp in Russia (especially in Moscow) and worldwide. Information about Slepushkin’s life is up today limited. The main sources in Russian are: Nikolai Parfenov Technique of Playing the Harp. Methode of prof. A. I. Slepushkin (1927), monograph Ivan Polomarenko Harp in the Past and Present (1939), Ksenia Erdely The Harp in my Life. Memoirs (1967, 2015), Vera Dulova Art of the Harp Playing (1975, 2013), Nadezda Pokrovskaya The History of the Harp Performance (1994), Ariadna Tugai Harp in Russia (2007). Most information has been handed down orally, therefore there are many variances. Obviously, each source is worthy in its own. Erdely and Polomarenko were contemporary with Slepushkin. Erdely knew him personally and wrote from his words, while Polomarenko most probably did not know him directly. Dulova acquired information from her teacher Maria Korchinska, who was in turn a student of Slepushkin. Pokrovskaya undertook intensive archive studies, which brought to light reliable materials. Not only were Parfenov and Slepushkin contemporary, the former was his student and devoted follower. Most recent research on Slepushkin’s life is included in the doctorate thesis of Maria Fedorova History of the Harp Class of Moscow Conservatory (2018) and is mostly based on archival sources, where newly confirmed documentary facts pertaining to A. Slepushkin’s life are highlighted. Aleksandr Slepushkin1 was born on 30 October 1870 in Sankt-Petersburg to an aristocratic family. Being a musically gifted boy, he received a good education, from an early age he played the violin, the piano, and the trumpet. However, his musical talent could not change his family’s plans for him: as he belonged to an aristocratic family, the young man had to follow a military career. In 1885 Slepushkin entered Aleksandr Cadet Corps (Aleksandrovskiy kadetskiy korpus), where in two years he finished the high school course. Education followed in 1887 in the prestigious Nikolaev Cavalry School (Nikolaevskoe kavaleriyskoe uchilische). Only men of noble origin studied in this elite institution, among them further prominent figures of Russian culture such as poet Mikhail Lermontov and composer Modest Mussorgsky. After finishing his studies, in August 1889, Slepushkin joined the Grodnenski Hussar Regiment (Grodnensky gussarsky polk), located in Warsaw. Three obligatory years of military service followed in summer 1892 with further education in one of the best educational institutions in Russia – Nicholas General Staff Academy (Nikolaevskaya Academia Generalnogo Shtaba). Upon finishing it in 1894, Slepushkin returned to Grodnenski Regiment and his military service continued on different posts there until 1900. From January 1901 to January 1902 Slepushkin served on Caucasus by Kutaisi Military Governor. On 16 January 1902, after almost seventeen years of military life, Slepushkin ended his service in the Imperial Army and in the rank of officer he enrolled in inactive formation of Guards Cavalry St. Peterburg county (Gvardeiskaya Kavaleriya Peterburgskogo uesda) (4, p. 86-92). No confirmed information concerning the period from January to October 1902 is available. Indeed, it is based on memoires of contemporaries. What happened in Slepushkin’s life after leaving his military career? Information in all above sources testifies that Slepushkin took harp lessons from August Insprucker before moving to Berlin. Place and time of these lessons differ and are not documented. Some sources indicate that Inspucker was palying in Warsaw Opera and Slepushkin took lessons in 1895 in Warsaw (3, p. 104 – 105), some others state – that “… upon returning to Petersburg he took private lessons from the second harpist of Mariinkiy Theater elderly German August Martinovich Insprucker …” (2, p. 79). All sources confirm that these lessons continued approximately for a year, after which A. Insprucker advised Aleksandr to study in Berlin with Wilhelm Posse. The second fact, which has been handed down orally, is about Slepushkin’s first contacts with the harp. According to all sources this happened when he was living in Warsaw, although the “actors” involved do differ. Erdely claimed: “Harp entered his life accidentally. Slepushkin told me, that once in Warsaw, where Grodnenski Hussar Regiment was located and where he served, officers were invited to the palace of a Polish tycoon. His niece played the harp, and her old small harp was standing in the attic. Aleksandr Ivanovich, being shown around the palace, saw the harp, tried to play it a bit and stayed attached to the instrument for his entire life” (2, p. 79). Dulova proposed another version. In Warsaw “… Aleksandr Ivanovich visited the house of his fellow, whose sister played the harp. Slepushkin liked the instrument and started to play it – self-taught. Soon he became the owner of the harp: in fact, the fellow gave him his sister’s harp because he owed Slepushkin some money (according to the memories of contemporaries, it was gambling debt). By that time, the fellow’s sister had abandoned music and was not playing the instrument” (3, p. 102). The similarities of these stories lead us to think, that Slepushkin was for sure introduced to the harp before deciding to quit his military career. From October 1902 the officer Aleksandr Slepushkin is mentioned in the students’ list of the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin (4, p. 95). He moved to Berlin to study with Wilhelm Posse. Wilhelm Posse (1852 – 1925) – brilliant harp virtuoso whose playing impressed Franz Liszt while Richard Strauss was consulting the harpist for his orchestra works. “I have probably heard something similar, but never better!” – told Liszt after his young friend performed transcriptions of Liszt’s music in Weimar in 1884 (7, p. 328). Posse, whom B. Vogel called “Liszt of the harp” (7, p. 328), was acknowledged by the public and critics as “the best living harpist” (7, p. 328). His playing was marked by “… most perfect instrumental technique, enriched with a sound, which was probably never poured out of the harp …. Posse is a poet on his instrument …” (7, p. 328) – so much was the harpist admired by his contemporaries. W. Posse – like A. Zabel, F. Poenitz and I. Eichenwald – was a student of Karl Ludwig Grimm, in his turn a student of J. Hasselmans and E. Parish-Alvars (1). Posse was one of the first European harpists, who introduced Lyon & Healy harp in 1895 in Brunswick, just a year after it was first presented in Europe in Amsterdam (5, p. 228). The moment when Aleksandr Slepushkin arrived in Berlin his new teacher was at the height of his triumphal career. This could only inspire decisive and determined Aleksandr. About Slepushkin’s life in Berlin, Erdely wrote from his words: “The teacher liked his enthusiastic student very much, studied with him a lot and stubbornly. Aleksandr Ivanovich said that he played the harp twelve hours a day, taking only short breaks for eating, walking and in winter – skating. Results were striking” (2, p. 79).

In full Aleksandr Ivanovich Slepushkin (Александр Иванович Слепушкин).

Fig. 15. Wilhelm Posse 1

How long did A. Slepushkin study with W. Posse? Dulova shared: “ As M. Korchinska told me … Slepushkin … finished the study course in four years and after successful graduation he toured Germany for several years”2 (3, p. 103). Erdely confirmed that “Posse admitted that Slepushkin was ready for professional life just after five years’ study and required him to start working as a harpist …” (2, p. 79). According to the lists of students of the Hochschule, A. Slepushkin was enrolled in Posse’s class from 1902 to 1904 (4, p. 99). Considering the differences of given facts, we can suggest that Slepushkin might have continued studying with Posse privately after graduation. In the years stretching from 1904 to 1908 the harpist discovered intensive artistical life. The beginning of which was not easy… Upon the request of his teacher, “Slepushkin joined a touring symphony orchestra in which each “principal musician” was to perform solo parts in the concerts. On one of his first concerts, the scheduled flutist was ill, and Slepushkin was asked to replace him. He became very agitated and felt that he would not be able to play. Upon entering the stage, he examined the harp and announced to the audience that during transport a pedal-rod had broken, which made his performance impossible” (2, p. 79).

As many musicians who started studying later in life, Slepushkin was insecure, including stage fright, and felt inadequate for the position thrusted upon him by his teacher. Self-discipline and firm will-power helped the harpist gain control over his lack of confidence. He later enjoyed brilliant success as a soloist touring Germany: amazing technique with beautiful singing tone impressed the public. In his repertoire were compositions of J. S. Bach, M. Balakirev, F. Chopin, E. Parish-Alvars, F. Poenitz. In the fall of 1908 Aleksandr faced stunning success at his London concert series: “English newspapers … wrote, that he played piano compositions of Liszt, Chopin, Balakirev and other composers with amazing easiness. Moreover, he found no difficulties in execution of chromatic passages, trills, etc” (12, p. 93). Following this success he was invited to teach at the Royal Academy of Music in London. It was a telegram of his sick mother asking her son to return home, that prevented him from accepting the invitation. In spring 1908 Slepushkin returned to Russia starting a new period of his life. Upon his return to St. Petersburg, Slepushkin “… brilliantly won the audition of the Court orchestra, the best orchestra at that time. But, he did not want to work under the court department, therefore he left for Moscow and in the same year, in April, he won the Bolshoi Theater audition …” (12, p. 93). The archival documents confirm that the audition, in which four harpists competed– Elena A. Alimova, N. Toyman – Shetokhina, Nikolai I. Amosov and Aleksandr I. Slepushkin – took place on 8 April 1908 (4, p. 101-102). Ksenia Erdely, in her memoirs The Harp in My Life, recounted the story of this audition from a personal letter of Klementina Baklanova, who was present.

“Slepushkin began to play Italian Fantasie by Paris-Alvars. My God! My God! Every atom of the air resonated, everything around rang out, sang. The commission was stupefied. … When Aleksandr Ivanovich finished Fantasie, there was absolute silence in the hall. Slepushkin was asked to play additional pieces, with the same results …. When Slepushkin left the hall, … I rushed out after him to ask him to teach me playing. No matter how I assured him that his playing had astounded everyone, he repeated “I doubt whether I passed. If they accept me, come tomorrow at nine in the morning.” Then the commission came out, and everyone began singing his praises” (2, p. 80; 3, p. 264).

1 Source: (7, p. 328)

2 V. Dulova dates Slepushkin’s travel to Berlin back to 1895, which is not correct, in the light of the hereunder documental confirmed information

Slepushkin played on his newly purchased Lyon & Healy harp – the first of its type to be brought to Russia. During his work at Bolshoi he performed in the orchestra, but also as a soloist and was active in different social projects. Among his colleagues and friends were composers Sergei N. Vasilenko, Mikhail M. Ippolitov-Ivanov, Yuri S. Sakhnovsky, conductors Vyacheslav I Suk, Sergej A. Koussevitzky, Aleksandr P. Aslanov, singers Leonid V. Sobinov, Antonina V. Nezhdanova, Margarita G. Gukova, violinist Nikolai K. Avierino, dancer Vera Karalli, among others (10, p. 46). Aleksandr Slepushkin was soon invited to teach at Moscow Conservatory. His students were Maria A. Korchinska, Nikolai G. Parfenov, Klementina Baklanova, Maria A. Bedelevich-Pushechnikova, E. Raiskaya, Evgenia Sulimova, Sofia Tauer among others. Maria Korchinska – after emigrating to Great Britain – continued to share and spread the principles of her teacher in Europe, Klementina Baklanova and Nikolai Parfenov were his followers in Russia. Parfenov worked at the publication of the methodical notes of his teacher and published the brochure Technique of Playing the Harp. Methode of Prof. A. I. Slepushkin. Slepushkin only taught for ten years, but left a profound imprint in the harp pedagogy and in the harp history in Russia and worldwide. In November 1912 Slepushkin was diagnosed with typhus – the illness which fatally affected his life. The following years a further shocking event occurred – World War I. As an officer, Slepushkin was immediately summoned for the military service. Thanks to his excellent education and linguistical talent he was allowed to serve in the military censorship commission in Moscow. He also continued to work with students. The last years of Slepushkin’s life did not receive documentary reflection. Aleksandr Slepushkin died on 30 November 1918 in Moscow.

Fig. 16. Aleksandr Slepushkin1

In sixteen years which he dedicated to the harp, Slepushkin achieved incredible heights. As a performer he expanded the boundaries of the harp to an unprecedented extent. “He played with stunning technical finish and marvelous sound. You could hardly believe it was the sound of a harp” (2, p. 79). He stepped in into the path of his teacher and continued to enrich the harp repertoire with piano compositions, which raised the reputation of the harp among the public, musicians and critics. As a pedagogue and methodologist Slepushkin was not only a devoted and consequent, talented teacher. He also introduced a new approach to sound production on the harp which, consequently, led to the establishment of a new technical and practical method of playing the harp. Looking back on the development of the harp in Russia in the 18th and 19th centuries, it can be stated that the traditions of the Russian performing harp school after N. Devitte – who merged the best achievements of Moscow and St. Petersburg origins in his creative work – were not continued by A. Zabel and I. Eichenwald. The new school, which they built up both in St. Petersburg and Moscow was based on and continued French-German traditions of R. N. Ch. Bochsa, E. Paris-Alvars and K. Grimm. Their activities were more oriented towards a transmission of the European harp culture to Russia. Consideration of Russian mentality, musical traditions and culture in general would play a minor role. It was A. Slepushkin’s teaching in Moscow which marked the difference between the “European” St. Petersburg school and, the Moscow school based on new principles. Except for this, its ideology also pivoted around the best traditions of Russian instrumental school, in its turn founded on the continuity of Russian cultural traditions and respect of Russian mentality. Not surprisingly, this system has attracted increasingly more followers. It was a milestone in the history of Moscow harp playing: the foundations of the Moscow harp school – in particular – and of the Russian harp school in general were laid down, thus affecting the development of harp history worldwide.

1 Source: (4).

Attachment 1. Appointed harpists to the Imperial orchestras in Russia in the XVIII – XX centuries (16, p. 139-140)

St. Petersburg

Moscow

| Potochniy F. | 1819 – 1835 | 1790 – ? |

| Fatchek B. | 1837 – 1840 | 1802 – ? |

| Akimov P. | 1838 – 1854 | 1818 – 1872 |

| Sokolov ? | 1856 – ? | ? |

| Danenberg F.A. | 1863 – 1878 | ? |

| Eichenwald-Papendik I.I. | 1864 – 1902 | 1842 – 1917 |

| Dmitrieva E.V. | 1881 – ? | 1859 – ? |

| Ciarlone G. | 1886 – 1906 | 1865 – ? |

| Ciarlone V. | 1886 – 1896 | 1869 – ? |

| Ome G.I.A. | 1898 – 1914 | 1873 – ? |

| Erdely K.A. | 1899 – 1907 | 1878 – 1971 |

| Anisimova N.D. | 1902 – ? | ? |

| Slepushkin A.I. | 1908 – 1918 | 1870 – 1918 |

| Mollica A. | 1915 – 1920 | ? |

Attachment 2. Professors at St. Petersburg and Moscow Conservatories till Soviet Revolution (1917)

St. Petersburg

Albert Zabel (1862 – 1905)

Ida Zabel-Rashat (1896 – 1910?)

Ekaterina Walter-Kühne (1904 – 1917)

Xenia Erdely (1913 – 1918)

Moscow

Ida Eichenwald (1874 – 1906)

Xenia Erdely (1906 – 1907)

Alexander Slepushkin (1908 – 1918)

Attachment 3. Compositions of Albert Zabel

Romance Op 6

Elegie Fantastique Op. 11

Fantasy on themes from Gounod`s Faust Op. 12

Pensée fugitive pour harpe ou piano Op. 16

Le Desir – Melodie Op. 17

Legende: morceau fantastique pour harpe ou piano Op. 18

Marguerite au rouet Op. 19

Ballade in drei Episoden: Die Erwartung am See, Die Begegnung, Der Abschied Op. 20

A la chapelle Op. 20

Reve d’Amour Op. 21

La source / Am springbrunnen Op. 23

Chanson de Pecheur-Barcarolle Op. 24

Marguerite Douleureuse au Rouet No. 2 Op. 26

Une Moment Heureux – Romance Op. 27

Warum? – Fragment op. 28

Murmure de la Cascade Op. 29

Romance sans paroles op. 31

La Capricieuse op. 32

Entr’act du ballet “Roksana” op. 33

Concerto c-moll for Harp und Orchestra op. 35

Tristesse d’amour Op.36

Valse Caprice for Harp, Op. 37

Without Op. Identification :

« Ein Wort an die Herren Komponisten über die praktische Verwendung der Harfe im Orchester“, Leipzig 1899

The Method for the Harp, Leipzig: Zimmermann 1900

Drei grosse Konzert-Etüden / Three Concert Studies (Supplement to the “The Method for the Harp”

Fantasy on themes from Donizetti`s Lucia di Lammermoor

Bibliography

1. Aber-Count, Alice Lawson (2001) Posse, Wilhelm. Grove Music Online. Date of access: 05. 04. 2020.

2. Erdely, Ksenia (1957, Reprint 2015): Arfa v moei gizni (The Harp in my Life). Moscow, Liumʹer.

3. Dulova, Vera (1975): Iskusstvo igri na arfe (The Art of the Harp Playing. Moscow, Sovetsky Kompositor (Soviet Compositor).

4. Fedorova, Maria (2018): History of the Harp Class of Moscow conservatory. On archival documents. Doctorate thesis. Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory.

5. Govea, Wenonah Milton (1995): XIXth and XXth Century Harpists: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Connecticut, London, Greenwood Press.

6. Kanemitsu-Nagasawa, Masumi (2018): Understanding chracteristics of the single-action pedal harp and their implications for the performing practices of ist repertoire from 1760 to 1830. Doctorate thesis. University of Leeds.

7. Krause, M. Wilhelm Posse. Krause, M. Wilhelm Posse. «Musikalisches Wochenblatt», Vol. 18, no. 27 (30 June 1887): 327, 328, 329. www.ripm.org.

8. Parfenov, Nikolai (1927): Technika igri na arfe. Metod prof. A. I. Slepushkin (“Technique of Playing the Harp. Methode of prof. A. I. Slepushkin”). Moscow, Gosudarstvennoe Isdatelstvo, Musikalny Sector (State Publishing House, Music Sector).

9. Pasetti, Anna (2008): L’Arpa. Palermo, Ed. L’epos.

10. Pokrovskaya, Nadegda (1994): Istoria ispolnitelstva na arfe (The History of Harp Performance). Nowosibirsk, Conservatory Nowosibirsk.

11. Pokrovskaya, Nadegda. Is gusar v arfisti. Ob Aleksandre Ivanoviche Slepushkine (From Gussar to a Harpist. About Aleksandr Ivanovich Slepushkin). Pokrovskaya, N. Is gusar v arfisti. Ob Aleksandre Ivanoviche Slepushkine. «Vestnik musikalnoi nauki», № 3 (13) – 2016.

12. Polomarenko, Ivan (1939): Arfa v proshlom i nastoyaschem (Harp in the Past and Present). Moskau, St. Petersburg, Gosudarstvennoe Isdatelstvo (State Publishing House).

13. Rensch, Roslyn (2007): Harps and Harpists. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

14. Serov, Aleksandr (1986): Articles about Music. Moscow.

15. St. Peterburgskie Vedomosti. Periodical: 22. 07. 1853.

16. Tugai, Ariadna (2007): Arfa v Rossii (The Harp in Russia). St.

Petersburg, Sudarianya.

17. Ukolova, Elena / Ukolov, Valery (2001): Raspyatiy na arfe (Crucified on the Harp: the Life and Work of Nikolai Devitte). Moscow, MAI.

18. Wolf, Ludwig: Johann Baptist Hochbrucker and the Paris Harp Mode. Ptivate copy.

19. Zabel, Albert: (1900): Method for the Harp. Leipzig, Zimmermann.

20. Zingg, Irina (2020): „Harp treatises of the second half of the 18th – first quarter of the 19th centuries: Establishment of professional performance“. Doctorate thesis. Gnesin Russian Academy of Music.